Two trophy skulls, recently discovered by archaeologists in the jungles of Belize, may help shed light on the little-understood collapse of the once powerful Classic Maya civilization.

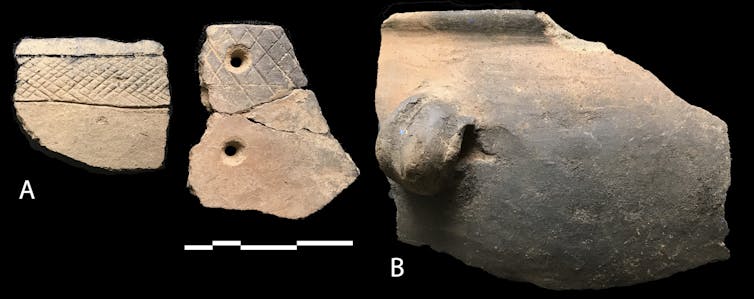

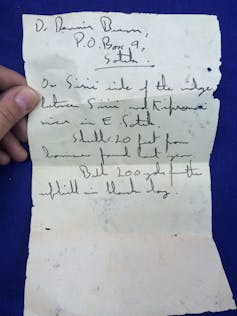

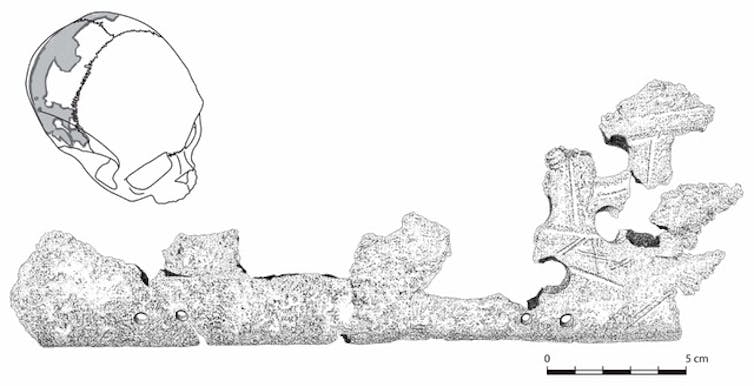

The defleshed and painted human skulls, meant to be worn around the neck as pendants, were buried with a warrior over a thousand years ago at Pacbitun, a Maya city. They likely represent gruesome symbols of military might: war trophies made from the heads of defeated foes.

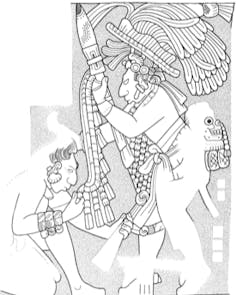

Both skulls are similar to depictions of trophy skulls worn by victorious soldiers in stone carvings and on painted ceramic vessels from other Maya sites.

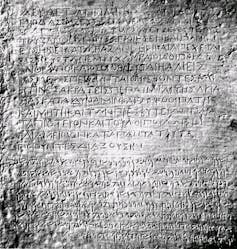

Drilled holes likely held feathers, leather straps or both. Other holes served to anchor the jaws in place and suspend the cranium around the warrior’s neck, while the backs were sawed off to make the skulls lie flat on the wearer’s chest.

Flecks of red paint decorate one of the jaws. It’s carved with glyphic writing that includes what my collaborator Christophe Helmke, an expert on Maya writing, believes is the first known instance of the Maya term for “trophy skull.”

What do these skulls — where they were found and who they were from — tell us about the end of a powerful political system that thrived for centuries, covering southeastern Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize, and portions of Honduras and El Salvador? My colleagues and I are thinking about them as clues to understanding this tumultuous period.

What ended a civilization?

The vast Maya empire flourished throughout Central America, with the first major cities appearing between 750 and 500 B.C. But beginning in the southern lowlands of Guatemala, Belize and Honduras in the eighth century A.D., people abandoned major Maya cities throughout the region. Archaeologists are fascinated by the mystery of what we call “the collapse” of this once powerful empire.Earlier studies focused on identifying a single cause of the collapse. Could it have been environmental degradation resulting from the increasing demands of overpopulated cities? Warfare? Loss of faith in leaders? Drought?

All of these certainly took place, but none on its own fully explains what researchers know about the collapse that gradually swept through the landscape over the course of a century and a half. Today, archaeologists acknowledge the complexity of what happened.

Clearly violence and warfare contributed to the end of some southern lowland cities, as evidenced by quickly constructed fortifications identified by aerial LiDAR surveys at a number of sites.

Trophy skulls, together with a growing list of scattered finds from other sites in Belize, Honduras and Mexico, provide intriguing evidence that the conflict may have been civil in nature, pitting rising powers in the north against the established dynasties in the south.

Piecing together the skulls’ social context

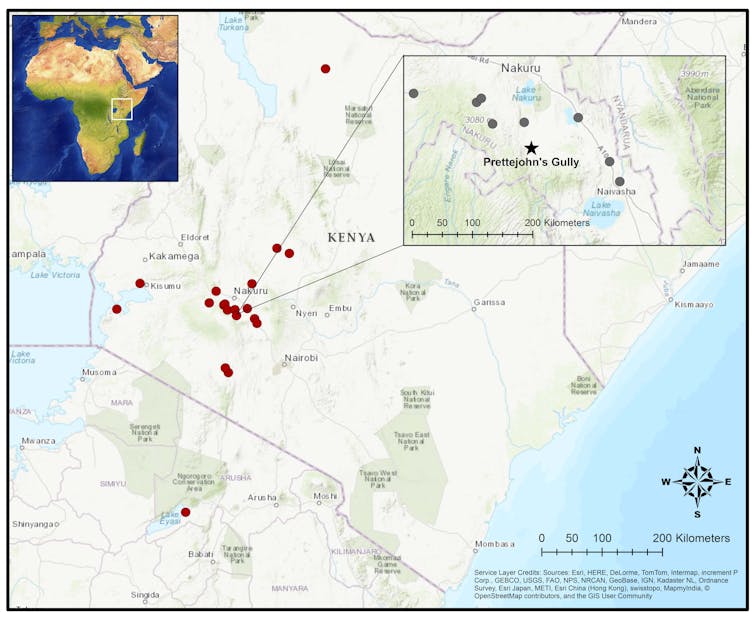

Ceramic vessels found alongside the Pacbitun warrior and his (or her – the bones were too fragmentary to confidently determine sex) trophy skull date to the eighth or ninth century, just prior to the site’s abandonment.During this period, Pacbitun and other Maya cities in the southern lowlands were beginning their decline, while Maya political centers in the north, in what is now the Yucatan of Mexico, rose to dominance. But the exact timing and nature of this power transition remains uncertain.

In many of these northern cities, art from this period is notoriously militaristic, abounding with skulls and bones and often showing war captives being killed and decapitated.

At Pakal Na, another southern site in Belize, a similar trophy skull was discovered inscribed with fire and animal imagery resembling northern military symbolism, suggesting a northern origin of the warrior it was buried with. The presence of northern military paraphernalia in the form of these skulls may point to a loss of control by local leaders.

Archaeologist Patricia McAnany has argued that the presence of northerners in the river valleys of central Belize may be related to the lucrative trade of cacao, the plant from which chocolate is made. Cacao was an important ingredient in rituals, and a symbol of wealth and power of Maya elites. However, the geology of the northern Yucatan makes it difficult to grow cacao on a large scale, necessitating the establishment of a reliable supply source from elsewhere.

At the northern site of Xuenkal, Mexico, Vera Tiesler and colleagues used strontium isotopes to pinpoint the geographic origin of a warrior and his trophy skull. He was local from the north. But the trophy skull he brought home, found atop his chest in burial, was from an individual who grew up in the south.

Other evidence at a number of sites in the southern highlands seems to mark a sudden and violent end for the community’s ruling order. Archaeologists have found evidence for the execution of one ruling family and desecration of sacred sites and elite tombs. At the regional capital site of Tipan Chen Uitz, approximately 20 miles (30 kilometers) east of Pacbitun, my colleagues and I found remains of several carved stone monuments that seem to have been intentionally smashed and strewn across the front of the main ceremonial pyramid.

Trophy skulls and power dynamics

Archaeologists are not only interested in identifying the timing and the social and environmental factors associated with collapse, which vary in different regions. We’re also trying to figure out how specific communities and their leaders responded to the unique combinations of these stresses they faced.While the evidence from just a handful of trophy skulls does not conclusively show that sites in parts of the southern lowlands were being overrun by northern warriors, it does at least point to the role of violence and, potentially, warfare as contributing to the end of the established political order in central Belize.

These grisly artifacts lend an intriguing element to the sweep of events that resulted in the end of one of the richest, most sophisticated, scientifically advanced cultures of its time.

Gabriel D. Wrobel, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.